Fiction

Prairie Grass by T.K. Howell

Battling the Bindweed by Lillian Heimisdottir

The Message in the Land by Jonathan Clark

She’d found him with nothing more to go on than a first name given at last call on a Saturday night. It showed a level of industriousness and determination that Sam respected. As for her name? Charlotte perhaps? She looked like she could be a Charlotte. It wasn’t in his nature to be cruel, but it didn’t hurt to get their name wrong when t

She’d found him with nothing more to go on than a first name given at last call on a Saturday night. It showed a level of industriousness and determination that Sam respected. As for her name? Charlotte perhaps? She looked like she could be a Charlotte. It wasn’t in his nature to be cruel, but it didn’t hurt to get their name wrong when they pulled this kind of thing.

The ranch sat on the edge of the Blacklands, on the lip of an openness that never seemed to end. The prairie grass in the paddock was baked thin. It was a poor diet and they were supplementing the horse feed. Indian grass spikes splayed out tall alongside switch grass, browning, fading. Every morning, Sam stared into the infinite emptiness of the prairie hinterland and thought of deep oceans. He’d been in the sea once. It terrified him. The wide-open space, the idea that something huge and monstrous could be moving down there beneath his feet and he would never know.

Charlotte—or whoever she was—approached with the rising sun at her back. It was a long way to drive out of town so early in the morning. She was a handsome woman. Not beautiful, as such. Handsome. Strong features set in a broad face, framed by deep brunette curls. She stalked the wooden paddock fence line toward him. She’d brought a man with her. He stayed back at the ranch gate for now, leaning against her maroon Datsun. Sam rolled his eyes and spat on the floor. So it was going to be like that, was it?

“Sam?” she said when she was about twenty feet away. He didn’t look over or acknowledge her. Instead, he watched the foal as it grazed. It watched him in turn, waiting to see if Sam would move, if it would need to react. The foal was Sam’s newest and he was working it slowly. That’s what the owners wanted now. Back when he first started, when he was only fourteen and learning from that old soak Hirsch, it was about getting them broken and getting them fit to be mounted as quick as possible.

“Sam, I know it’s you. A friend said you worked out here.”

“Ma’am.” He touched the brim of his hat. He was always amazed at how far such a simple gesture could go. He knew it was running into folksy, Southern, self-parody. But manners were manners.

The woman hesitated. “You didn’t call me.”

“Don’t believe I ever made any promises to do so, Charlotte.”

“Katie,” the woman huffed. “You know damn well it’s Katie.”

It was early but already he was tired. Bone tired. He wasn’t so young any longer. Fatigue. It was hard work, he was getting older, that was all. Perhaps he should cut back on the drink, on the bars, on the Katies and Charlottes.

“What can I do you for, Miss damn well Katie?”

“You didn’t even reply to my messages. And you haven’t been back to that bar since. You said you liked me.”

Sam shrugged but didn’t take his eyes from the foal. “Woulda thought it was obvious I did. Look, I wasn’t looking for anything else. I’m not that kind of guy. I was quite clear.”

“I guess you got what you wanted, is that it?”

“Isn’t it what you wanted, too?” Sam asked, puzzled.

“Yeah, but…” Katie hesitated. “But upping and leaving like that under cover of night. Not a word after. It makes a girl feel grimy. Used.”

“Well, you shouldn’t. You’re a fine woman, you should feel appreciated. There’s no harm to it. No foul. Anyone judging you can go to hell,” Sam said.

“I’m judging myself.”

“Why?” Sam’s brow wrinkled.

“Maybe… maybe because it’s what people do. What grown-ups do, at any rate.”

“Ma’am, I gotta get back to work. Now, who’s the goon down by your car? Why’d you think you need a bodyguard, huh? He your little brother?”

“Who?” Katie turned and squinted back toward the rising sun, toward the gate. “Where?”

“Hmm.” Sam watched the man as he continued to lean against the Datsun, arms folded. He was young and wiry looking and if it came to it Sam was sure he’d be out of puff before the kid had warmed up. He could throw a punch, maybe even two or three, but he couldn’t brawl no more. Brawling took stamina. The Datsun kid wore a dark suit that made him look a little like an old-timey preacher and a little like a tax inspector. His shoes gleamed in the sunlight, even at one hundred yards. Sam was so captivated by him that he didn’t register the rest of Katie’s speech until she, too, seemed to flag in the morning heat.

“Ma’am, you’re going to have to leave now. This is a workplace and my boss wouldn’t take kindly to strangers on the ranch,” Sam lied. Markovits couldn’t give a hoot. “Maybe I’ll see you around.”

“I don’t know whether to laugh or cry,” she said, exasperated.

“Try for neither?”

“You’re going to die alone,” Katie signed off. It wasn’t original and it didn’t cut him none. He never understood it. Why would he shack up with someone just for the sake of having company? Loneliness wasn’t his enemy. Keeping house with another person, making nice every morning, and trying to think of brand new conversations over breakfast? It seemed so deadly draining.

***

He was filling up at the station when the Datsun Kid appeared, leaning against the hood of his truck. Leaning against vehicles seemed to be his primary disposition. Sam’s mind had gone wherever it was minds go when the hands were pumping fuel into an empty tank. It was topping thirty degrees and the dizzying scent of petrol was heavy in the air. The fumes hit and the back of his brain felt like honeycomb dissolving in hot milk. He turned to put the nozzle back and nearly lost his balance, the head-rush tipping his senses upside-down. When he’d regained his composure, there was the kid. Now he got a good look at him, he wasn’t quite so young. Mid-twenties, maybe. He had smooth skin and full, fair hair slicked back over a bare head. Sam’s skin had been just as smooth once, before he had been at the ranch a while. He had liked the way it tanned in the sun, how the dry wind weathered it like sandpaper. From cherub to hardened old cow-puncher in two years on the ranch. It had given him something, he didn’t know what. Gravitas? Some innate essence of masculinity that gave him an edge, out there in the night-time world. Through his late twenties and early thirties, he had studied and admired those lines, the toughness of them. Moisturiser was a sick joke played by advertisers on young men who didn’t know the value of a face that had been lived in.

Now, with the once-distant shores of his forties homing into view, Sam looked at those lines and all that sun damage and knew there was no going back. The pattern was set. He would get old, and quickly.

“Fine day. Fine day. Short skirt weather, huh? Beautiful. Can you remember that one summer? Those long, bare legs that wrapped around you and her lilting accent as she whispered in your ear? Oh, the discoveries. There’s nothing to match it, is there? Finding it all out for the first time? Depreciating returns ever since.”

Sam gripped the door frame of his truck and blinked. The kid tossed a coin and caught it. Tossed it, caught it. Over and over. Then he tossed the coin to Sam, who reacted too slowly, grabbing at empty air. It skittered to the ground, spiralling inward with a high, thin sound. When he looked up, the kid was gone. Sam stared at the space where he had been, then paid the attendant and gave the young man no further thought.

He drove on, replaying memories of Katie. But the memories were washed out, fading. Like two bad actors on a stage, it did nothing for him. It had only been a fortnight ago and it was already going, going, going. In the moment, it was everything. But after, it drifted on the breeze and into the prairie wilderness becoming thinner, until it was gone, gone, gone. How many had he forgotten?

The road into town was straight and empty through a flat expanse of biscuit-coloured soil and desiccated bluestem. His eyes sagged as he watched the still horizon. One swing of his arm and he could veer off into the tallgrass and just keep going, going, going out into the deep blue sea of wild indigo.

No. This road was his long, narrow bridge that led over the unknown fathoms. He wound down the window for a sharp snap of dry air and drove on, the sun sitting heavy over the truck. It reflected off the chrome wing mirror and dazzled his eyes. It blinded him for a second and he nearly missed the kid.

He was standing at the side of the road up ahead. Waiting. Hands in pockets. Bare head and dark suit in the afternoon sun. Sam pulled over and without a word passing between them, the kid got in.

“Where are you headed?” Sam asked. The kid didn’t answer.

“Are you following me?” Sam snapped.

“Are you following me?” the kid grinned. “Town. We’re heading to town, of course. I think we better get a drink. You’re looking a little tense.”

Sam didn’t argue. “You gonna tell me your name, or do I have to guess?”

The kid smiled beatifically but again, didn’t answer.

“John, right?”

“Why John?”

“Because you look like a John. That was my father’s name. It’s a solid enough name. Solid enough man.”

“I bet he was the kinda guy who thought you could learn all you needed to know about a man by sidling up to him on a Sunday afternoon and asking ‘what’s the score?’ Mine was like that. Talked about sowing wild oats a lot. Don’t you remember me? It’s Jack. I’m Jack.”

Sam could only see Jack in his periphery. It was a long, straight road but he wasn’t one to take his eyes off it. He caught the suggestion of the kid’s smooth skin and unweathered face, the full head of blonde hair. His knuckles whitened on the steering wheel.

“We’ve met?”

“Jasmine,” Jack said, ignoring him. “You remember the half-Mex girl who smelled of Jasmine?”

And Sam could. He could see her face clearly, even though it must have been fifteen, twenty years ago. Clearer than Katie had ever been. The scent was there, hanging in the air of the truck, saturating the upholstery, seeping into his clothes. He twitched his eyes at either side of the road, but there was nothing there but the same old brown earth and scrub, certainly no jasmine growing by the tarmac. He saw Jack smile and repeat “Jasmine”, the scent came on stronger and Sam was gone. He was back at a college keg party, back in the days when he threw a mean spiral and could hit any guy on the field from fifty yards. Back before everything started to ache.

“Who are you?”

“The taste of her sweat, you remember? The way she wouldn’t take her top off. You remember she had a scar? Heart surgery when she was younger. Made her anxious.”

“It’s going to be like that, is it?” Sam’s lines wrinkled. “I guess I really need to get some rest.”

“Do you remember her name?”

“No,” Sam answered honestly.

“Me neither. Have you stopped keeping score?”

Sam’s mouth twitched uncomfortably. “I grew outta that, I guess.”

Jack chuckled. “Really?”

“I don’t… I forget. No, it was immature. I don’t even know who I was in competition with. Myself I guess. And I thought maybe that was the reason for it. To beat the other kids at college, you know? Now, I just like it, I suppose. The physicality of it. Sex as sport. I don’t see why they gotta try and make me feel ashamed of that. I don’t see why they gotta play out some fairytale happy ending for us every time they come look for me … I see you. I can see what you’re thinking.”

“It’s not your fault they take you at your word,” Jack said. Sam believed he heard an edge in the kid’s voice.

“I don’t lie to them,” he said. “I don’t make any promises. Did she send you? Katie?”

Jack shook his head. “It’s not your fault they don’t have the sense they was born with. Tsk. You tell them a story, you tell them about your work, you spin an old tale about the time that Overo died right underneath you when you’d ridden two hours out into the prairie just because you were young, just because you could, just for something to do. How you ran out of water, thought you was done for. How many times have you told that same story now?”

“Habit, I suppose. It’s something that happened, is all.”

“It all happened exactly that way, did it? You alone out there under then sun? And you don’t think they hear that and imagine themselves in-between you and the great wide open. Tsk. You know what you’re doing.”

Sam grimaced and then rocked the steering wheel back and forth a few times, veering in and out of the lane dividers. His head bounced from side to side, catching the headrest. When he levelled out, Jack was still there.

“They warned me this might happen,” Sam said.

“Tsk.”

Up ahead, a car appeared out of the shimmering heat. It was the only other car on the road, the only car they’d seen for five minutes. Sam turned the radio up as loud as it would go and stared straight ahead. He leaned forward until Jack was in his blind-spot.

The sound of the car dopplered as it passed. Low-high-low. Sam blinked and they were in the parking lot of a downtown bar. He was stretched out in the back-seat of his truck and Jack was gone. It was still light out and would be for another three hours. He walked in and Jack was sat at the bar with two beers, waiting for him.

“You needed to rest,” he explained.

“Long day,” Sam answered. He must have slept a while in the parking lot. Didn’t feel like he’d slept. Everything still ached. His joints were stiff and when he moved his arms, twitched his fingers, he had the strangest sensation that they weren’t quite where he expected them to be. It took him two grabs to take the beer and when he looked down at his hand gripping the cold glass, he was sure for a moment that it belonged to someone else.

“They always wanna fix you, right? They think you’re a damaged kid inside that they can mend if they just show you enough love. Forget it. Remember bringing that stallion back from Benton City? You remember the daughter? She knew you were headed the next day. Those are the best ones. Heedless. No shame when they think they’re never gonna see you again.”

Sam smiled. “She sure was something. I had a rash on my back from the straw bales for a week. Had to sleep on my chest it itched so bad.”

“It was worth it.”

“It was.”

Sam finished his beer. And then another. His eyelids began to feel like lead shutters.

“I think you should sit tonight out,” Jack said, slipping his arm under Sam’s shoulder and walking him back to his truck. “Sleep up. You’re getting a little long in the tooth to follow a day on the ranch with a full night in someone else’s bed.”

“Like hell-”

“Easy,” Jack said and before Sam knew it, he was laying down on his back seat again, and then it was sunrise and he was driving back to the ranch, the same biscuit-coloured dirt, the same tallgrass. His mind wandered and then he was working the foal in the pen, trotting it on a long rein. It was coming along, he turned and she would follow. She was trying to comply and he eased off the pressure. It was beginning to understand what he wanted from it. When to stop, when to move.

He didn’t see Jack for the rest of the day and long before sunset he fell asleep in the little nook above the stables, draped in horse blankets, soothed by the gentle whinnying below. He woke after sunrise, wondering if he would ever see night-time again.

He took a simple lunch of eggs, bacon, and fried tomatoes at the truck-stop Diner two miles down the Highway. Katie, or Charlotte, or someone else he didn’t recall, was sitting at the counter. She pretended not to see him. Outside, the hot baking sun had given way briefly to a thick band of white clouds. Disney animation clouds that you could reach out and pull a handful of candyfloss from. They sat over the prairie like God’s eraser, ready to scrub it all out until it really was a featureless void.

Jack slid into the seat opposite Sam without a sound. With no signal or word passing between them, the waitress deposited a hot cup of black coffee on the table in front of him.

“You remember the cheerleaders? After the game and fresh from the shower and so ripe and you barely had to say a word and they were in the back-seat of your dad’s pickup, your hand up their top? You’d just been knocked around a pitch for three hours, beaten and tackled and it hardly touched you, didn’t feel it once you were out of your jersey. Now? It’d kill you.”

“Go away, kid. Leave me alone,” Sam snapped. His hands were holding the cutlery, slicing, cutting, putting food in his mouth. He looked at them, didn’t recognise them, wasn’t so sure. They were an inch or so wide of where his brain was telling him they were. If his hands could be in the wrong place, the whole world could be off its axis.

“Stop following me. Won’t you please quit following me?” Sam’s voice had a strained quality. He was shocked to feel the prick of something in the corner of his eyes.

“A blonde, a redhead, latino, black, asian, hippy, housewife, harlot. We gathered quite a collection.”

“That’s not what I was doing,” Sam faltered. “I was just having some fun.”

“Tsk.”

Jack looked out the Diner window, past the cars rolling down the Highway and out across the Blacklands. He was looking at it the way a man looks out from the stern of a ship at home port retreating into the distance.

“Say, you wanna come for a walk, Sam?”

Sam followed Jack’s gaze. His heart beat a tick faster. The eggs and bacon seemed to sit in a hard lump halfway to his stomach. He could feel the sweat at the base of his spine.

“No… no, I don’t, thank you,” Sam stammered. He found that nothing could compel him to turn his head and look at Jack, to chance meeting his eyes.

“That’s OK, I’m in no hurry. You ever think about the old cowpokes, Sam? You ever think about how they broke half-wild Mustangs by the hundred? Sounds romantic, right? Until you think about what they had to do. How would you break an adult horse that had only ever seen humans as something to run from?”

“There’s no call for that nowadays. No need.”

The Diner was filling up with a lunchtime crowd of truckers and ranch hands. The burble and chatter had been quietly rising and now, suddenly, it had become unbearable. Sam paid up and left. As the door closed behind him, the sound cut off like a chainsaw thrown into a lake. He was standing alone, looking up at a sky of white clouds the size of continents, the only sound the occasional rush of a car shooting past at eighty. He could walk off, right now, into the waves of tall grass. He could vanish out there, alone. The thought crept in and caught him unawares. He shrank from it, turning back to the Diner. Jack sat in the window, nursing his coffee. He gave Sam a toothy smile and nodded. Sam drove back to the ranch.

Markovits called across the paddock to him that afternoon, called him into the rotting old portacabin that sat behind the stables and served as his office. The ranch had money, and there were big, spacious rooms, but the boss had been in that portacabin for twenty years and nothing short of the roof collapsing would shift him. It smelled of moulding tax receipts and last week’s lunch.

“You OK, Sam?” he asked. “I noticed you was limping a lot this week, the ache come back? You should go see a doctor. You know you’s insured, don’t you?”

“I’m fine, boss.”

“You don’t have to prove you’re the toughest S.O.B. going no more, you know? And I don’t want you suddenly keeling over and me losing you for months when it could be an easy fix.”

“Just dog bone tired, boss. Not been sleeping too good, I think.”

“You think?”

“Yeah,” Sam answered and that seemed to be about all there was to say.

“Well… take it easy out there, Sam. I don’t mind a guy getting loaded, but you been coming in some mornings I can smell you from back here. Like I say, go easy.”

“Sure, boss. Sure.”

Markovits looked down at some imaginary paperwork and waved him away, a difficult conversation half-had, his moral and professional duty upheld to the smallest degree.

The foal came along quickly that afternoon. It was nowhere near mounting, but he could see the end in sight, the point when he could finally release the pressure and rely on command alone.

After an hour, he took one of the hacks out on a ride through the paddock to shake his muscles loose, remind them of the strength they had. With every step, his back jarred, his hips ached and pain crashed up his spine and into his hindbrain. He sat up straighter and kicked the hack into a trot, forcing the pain down, down, down until it was gone, gone, gone. But it was never really gone.

He took a well-worn path through the paddock and beyond, out into the dusty soil and rock that dipped into a crater for a half-mile at the reaches of the ranch. There had been an attempt at a quarry there many years ago. What they’d hoped to find was anyone’s guess, but the land had never really recovered. He slowed the hack, picking through the uneven ground. For five minutes everything else disappeared from view as they trudged together through the shallow bowl of rock and brush. He couldn’t see the ranch, couldn’t hear the Highway, even the sun seemed to vanish. All he saw was the sky and the land and the place where the two met.

When he reached the small ridge at the quarry’s end, he turned the horse and looked back at the ranch, the paddock, the foals. It seemed so far away, and yet it was barely a mile. He watched, testing his eyes, seeing what features he could pick out. His eyes, at least, hadn’t failed him. They had always been sharp. He must have gone further than he thought. The ranch was not the Markovits ranch. He didn’t recognise a single feature. Someone was working a foal on a long rein in an open pen, but Sam didn’t know them.

“I’ll take you back.”

The voice didn’t startle Sam. He’d been expecting it. He turned the horse and Jack was waiting, the long grass up past his waist, yellow-green against the immaculate tar-black of his suit. Sam dismounted and left the hack untethered.

“Will it take long?”

“Yes. But it’ll be safer if you come with me.”

“For whom?” Sam asked, trying to work a twinkle into his eye. Jack didn’t answer, turned, and walked. Sam followed and was quickly swallowed up by the grass.

The hack waited for five minutes and then muscle memory kicked in. It turned and made its way back to the ranch alone. ☐

The Message in the Land by Jonathan Clark

Battling the Bindweed by Lillian Heimisdottir

The Message in the Land by Jonathan Clark

The heat. The light. The midst of a drought, already the stuff of legend.

He roamed the land like an animal in migration. As if something in his body was called by a drive long since folded into his species. He wore short sleeve button ups and cargo shorts, a sports watch that left its mark in a tan line.

He didn’t use the Subaru’s air co

The heat. The light. The midst of a drought, already the stuff of legend.

He roamed the land like an animal in migration. As if something in his body was called by a drive long since folded into his species. He wore short sleeve button ups and cargo shorts, a sports watch that left its mark in a tan line.

He didn’t use the Subaru’s air conditioner. He rolled down the windows, letting the wind whip through him. The dirt rose off the roads and caught in his sweat. He arrived at destinations dirty, damp, ready to work.

The work: to scan the countryside in search of lost civilizations. The drought, in the third month of its siege, had burned all the grass and crops to a brittle brown. But the grass grew green where old walls and ancient post holes were, the soil there retaining water from the features underneath.

The past, the only thing that could thrive in such a present.

He traveled up and down the Mississippi, the continent’s legendary artery. It was always nearby, in view or just behind the next scrim of trees. It felt right in a drought to orient yourself around a wide river—especially so far away from the university, his favorite bar, the California landscape that he’d known since he was a graduate student.

He pulled off the highway just before East Saint Louis and found the motel that matched the email. It sat long and flat, its mid-century signage faded like bleached bones, the remnant of a former glory. The reader board below it declared:

Long Last Motel

Vacancy

He checked in and received his key and entered the dark room in a daze—hair blown wild, luggage baking in the backseat of the Subaru.

He fell back onto the bed, arms spread out cruciform. He stared into the ceiling. It reminded him of two years ago, how he stared at ceilings then, when the divorce had ended the world—or just his portion. At least this ceiling wasn’t spinning.

That evening, he skimmed notes on Mississipian culture and the builders of Cahokia. He read about their lives, the way things might have been. An entire way of being now gone. How does it feel, the end of civilization? It’s that kind of question that keeps you coming back, as if the next unearthed pottery sherd might reveal the secret unity behind the dazzling diversity of all human existence, grant direct access to the minds of those people building mysterious mounds in what would one day be called America. The surviving material could never get you close enough to know, but he liked to wonder.

His phone buzzed. Unknown number.

“Hello?”

“Gabe.”

The voice hurt. Maybe Margaret’s voice would always hurt—how a wife can turn into a wound.

“It’s you,” he said.

“My whole life.”

“How’re things?” he said.

“Sorry for calling. I just need to tell you.”

He shifted the papers off his lap and scooted down into a lying position on the bed. Again, the ceiling.

“Surprised you got me. The service is bad here.”

“Are you okay?” A familiar question of hers.

“I’m okay,”

“It’s the house. We had to evacuate.”

“I heard about the fires. Bad this year.”

“It took the house.”

The next morning, he fueled up down the road, grabbed a Gatorade and cheese sticks and stood in line.

Then hours of driving and surveys.

He stood on top of a hill and read the land, looking for green in all that brown. It would tell him humans built there. Claimed some space, erected shelter, placed wood in the earth that would one day hold that extra bit of water—how just a little bit of water makes all the difference in the world for the things that live here. And how no matter what you build, it will be destroyed, leaving a scar of green grass until, one day, not even that.

He strained his eyes into the binoculars. But all he thought of was his old house back in California, years since he’d last seen it. When he moved out, with his head low and the pieces of his days all apart, he thought he’d never live in a house again. What does a man alone need a house for? He needs only his car, some money, the use of his limbs to strangle a living out of the world that tries, oh how it tries, to strangle the life out of him.

But in the aftermath of the divorce, there was no vivid struggle, only a vague, deep doubt. He asked himself questions like What am I doing?and these questions caused even the simplest duties to go untended for months. His mind spread out in long tendrils of thoughts that didn’t do him any good, did no one any good. But he liked to wonder.

His old house—as real as the heat and dirt and sky around him, if not moreso. The argument in the kitchen about the student. The argument in the bedroom about the time spent at the university, the long hours and what they meant.

But there was no house. No white cabinets, no built-in shelves, no forest green shutters giving rhythm to the front face, no front face—every detail eaten by the fire that was gorging itself on California. A mighty Cape Cod, all wood, all gone.

What did the arguments matter? The infidelities? The reconciliations? The humiliation and rage and guilt and love that seeped out into the walls? Did they rise into the night sky with the smoke?

The land reasserted itself. What was that out in it? A green rectangle sketched in the field with undeniable corners. A possible site, Mississipian or, perhaps, a settler’s house. Too soon to tell.

He finished checking the panorama in front of him as a formality. Soon, he was in the Subaru and bouncing down a dirt road to the rectangle. The only house he passed on the way squatted against the sun’s heat and light. Its windows, blinding squares.

Finally, the road turned and became a straight shot to the spot in question. He picked up speed.

Large rocks protruded out from the road, like the backs of obscure creatures that lived in the earth, fought on its behalf—how a glimpse can awaken a myth, bear a legend.

The Subaru rose and dropped.

A groan and hiss.

He stopped and got out. The front driver side tire sat half flat, the rest of its air going fast. He stood in the middle of the dusty road and looked off to his destination and back to the tire.

His shoulder blades pressed into stony dirt as he lay down to examine the damage. The front axle was bent, mangled by one of the large rocks the Subaru couldn’t clear. It would need a tow.

He grabbed the Gatorade and drank, his sweat in full force. He pulled out the phone. No service. Just passed one o’clock. It would be the heat of the day soon, as if it could get much hotter.

But there was a house a little ways back. He could walk to the site and then turn around to get help. He sighed and took the last drink from his bottle and walked down the road to the green lines.

He stood before the patch of land, insects roaring. He climbed over the barbed wire fence at a T-post and considered the formation. To see it in person never got old—the signs of life from long dead humans. It made you feel like you could be in all times at once, or that maybe, in some way, you were there, that it was you who built this shelter, as if you were all people who ever lived, if only you could remember.

But this was a fleeting awe. The rising heat made everything blurry, confused.

He focused. He saw the lines meeting at right angles, that all-too human feature. He wondered how the men and women who lived there might have fought the heat, how they would enter this shelter for shade. And then, also, he wondered at the simple miracle of shelter itself, how it was one part of a long chain that led to a summer like this. When the built environment became our only home, it was only a matter of time until the earth no longer was.

And as he stared into this rectangle, his mind rose above the earth to visit another house hundreds of miles away, one taken back by fire. Fire, shelter, death, the passing of time. What did the builder of this home think of these things?

But the heat and light.

He took notes and snapped pictures.

Satisfied, he turned toward the house that stood up the road, and he walked, dropping his things off at the car on the way.

The house: two stories covered in crumbling, gray asphalt tiles. Silence, a bad sign—how the human ear hungers for the human voice in crises large and small.

He walked up the porch steps and opened the screen door and knocked. Nothing. No other house for miles, and he’d already sweat out his Gatorade and every last drop of water he’d ever drank.

He cupped his hands around his brow and looked through a window. Furniture sitting dumb in the dark.

“Hello?” he called.

Silence.

He stepped off the porch and walked the perimeter, looking for signs of life.

“Hello?”

The sun on his skin. The panting heat.

In the back were narrow steps leading to a door, a rail made of piping. He scaled the steps in a single lunge and knocked.

The sun pressed.

He reached down to the knob.

Locked.

His heartbeat broke into a sprint.

He grabbed hold of the pipe rail and kicked the door. It rejected him, but allowed some promising give. He kicked and kicked and kicked.

He kicked again. The rail jerked out of place—he fell with it into the brittle grass.

The tumble awoke a new mode of being in the man. Mad with heat. Get into the house.

He jogged up to the front porch and took off his shirt and wrapped it around his arm and swung his elbow hard into the window and the pane shattered and he cleared the remaining glass as best he could and he stormed into the living room like a soldier given orders to kill everyone in sight and he felt the warm air inside and he searched the house for a sink and he did not even notice the dust and mouse feces and spiderwebs and he saw the kitchen gleaming and he stood over the sink and he turned the faucet as if this was the action that his entire life had always been moving toward.

Nothing.

He stepped back, guts rising into his throat. He turned to the rest of the house. Where would water be? He left the kitchen in search of the bathroom, the toilet’s tank.

He left the house slaked, head cleared of any history, of any shame or pride. He made his way to the car.

Inside the Subaru, he rolled up the windows and ran the air conditioning and strategized how to get back to the motel, and he did this in a wordless fugue. And then his eyes began to close, and then darkness.

He snapped awake—the world transformed into the failing, purple light of a late summer evening. The car was still blowing cool air. He felt his body, his half dry clothes, as if to make sure he had not died.

And in the air, a smell.

Smoke.

He stepped out into the road, into the heat. He turned around, and in the distance behind the house, the strangest orange glow.

A great wall of fire on the move. However fast such walls spread, he did not know.

Here of all places, a fire.

A fire, less distant than before.

He turned to the horizon where his body knew the river was, and he ran, he ran, he ran.

Battling the Bindweed by Lillian Heimisdottir

Battling the Bindweed by Lillian Heimisdottir

Battling the Bindweed by Lillian Heimisdottir

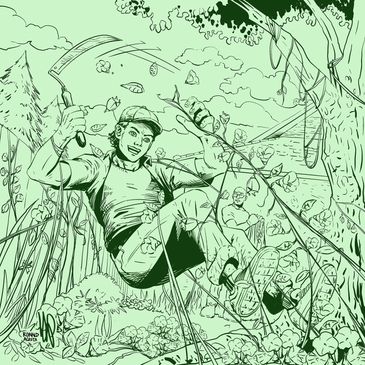

I had never seen a man use a sickle in real life until we moved into the house on Primavera Avenue. Sure, I had seen sickles in cartoons and animated movies, but I didn’t know that you could buy tools like that at the local garden centre. The reason my father had purchased such an antiquated gadget, was that we had rented a house with an

I had never seen a man use a sickle in real life until we moved into the house on Primavera Avenue. Sure, I had seen sickles in cartoons and animated movies, but I didn’t know that you could buy tools like that at the local garden centre. The reason my father had purchased such an antiquated gadget, was that we had rented a house with an enormous garden that had been left unattended for over a year and now looked like an unsurpassable jungle.

So, my father had gone out to buy all kinds of appliances to attack the massive bushes and impenetrable weeds that were entangled beyond comprehension. He had acquired trimmers and shears, a rake and a shovel, an electric hedge-cutter and some hand-tools to rotate the soil. Then there was this funny looking thing that I recognized from pictures of ancient farming in my history schoolbooks.

“Wow, let me see this,” I said and grabbed the tool to inspect it.

“Careful, it´s sharp,” my father warned.

But I had already removed the cover from the blade and started hatching the thistles, which were over five feet tall and fell like little trees as I chopped them down.

“Here, take the shears and start cutting the hedges,” my father commanded. “Or better yet, get the rake and gather together the branches and the leaves. I’ll do the cutting.”

He started trimming the hedges with the big shears and soon cut-off twigs and leafy branches came flying on the ground. I did the best I could to rake them together and stuff them in large plastic bags. It was a tedious task and I was perpetually poking holes in the bags with the pointy ends of the cut-off branches. Also, I was constantly scratching my hands and forearms, even though I wore thick working gloves and tried to cover my arms with my shirtsleeves.

“Take care not to rip the bags or everything will fall out of them,” my father shouted when he saw how clumsy I was.

“The branches are too big. I can’t get them properly in the bags without tearing the plastic.”

“Let me see that,” my father said in an annoyed tone, as he took over the job.

The way he did it seemed to work fine. He could fill the bags without making a single hole in them. So I decided to let him just take care of the whole procedure and snuck off to another part of the garden where I was out of sight. And of course, I took the sickle with me. I was really fascinated by this magical-looking tool.

I walked to the wall that enclosed the garden and started to look for lizards and other creatures that might be living in the cracks, but apart from a few spiders and horseflies I saw no sign of animal life. So I took to inspecting the plants closer. I kicked a few large weed stems with my foot, which resulted in them releasing huge amounts of a dust-like material that was foul smelling and stung in my nose and made my eyes burn.

Then I noticed the tangles of bindweed climbing up the wall and the tree trunks. I actually found it quite pretty with its white trumpet-like flowers, but it was clear that it was a brute of a plant, out-competing all other vegetation in the garden. The bindweed crept along the surface of the soil, climbing fences, other plants and whatever else it did encounter, forming a dense, entangled mat of greenery. Entwining its way around other plants, this super-weed eventually strangles them and takes over the whole vegetation.

I took the sickle and started hacking at the bindweed. First gently and carefully, just to see if it would somehow defend itself, by releasing a foul-smelling, itchy powder, like the other weeds. Then gradually I chopped harder, taking down larger parts of the entangled web of green rubbery weeds.

“Take that, you creepy monster,” I hissed as I mowed the weeds to the ground.

I hacked and beat the bindweed and tore out large heaps of it, and while I did so I got more and more excited. I began picturing myself in a fight with an invasive species of alien creepers. I was Earth’s only hope in the battle against the murderous invader. I must have gotten carried away, for suddenly, while tearing up a large chunk of greenery, I fell on my back and was instantly covered by the creepers and heaps of leaves from the plant. While I struggled to get up, I felt how the bindweed tried to wind itself around my legs and arms, making its way to my neck, ready to choke me and take over my body. I let out a loud scream and tore the disgusting vines off me as fast as I could. With the sickle still in my hand, I was prepared to defend myself against this ferocious attacker. I lashed out and hacked and tore the leaves, while stamping with my feet on the stems, trying to kick the roots out of the soil. All the while, I screamed profanities at the green assailant, ensuring the aggressor that it would not get me alive.

“What on earth are you doing?” My father stood looking down on me with an expression of anger and incomprehension on his face.

“Give me that thing,” he said and snatched the sickle from my hands. “Go, take

the rubbish bags out.” He shook his head in disbelief and muttered something incomprehensible.

I walked away from the bindweed, thinking that I had missed the chance to eradicate the danger it presented to our garden and the whole of the country. Nobody would be able to stop its spread now, and before long Earth’s surface would be covered in green creepers that would annihilate all other life on the planet. If only I could get my hands on that sickle again!

An American Sandwich BY Simone Martel

Twice as Much and Twice as Hard BY Lillian Heimisdottir

Battling the Bindweed by Lillian Heimisdottir

The view from Aunt Carol’s row house took in streets of more row houses and, in the high distance, a nuclear power plant looming over a cow field. “I don’t mind,” Aunt Carol said. “You get used to it.” But Susan heard the power plant ticking in her restless, jetlagged sleep and startled awake in the attic bedroom next door to her cousin

The view from Aunt Carol’s row house took in streets of more row houses and, in the high distance, a nuclear power plant looming over a cow field. “I don’t mind,” Aunt Carol said. “You get used to it.” But Susan heard the power plant ticking in her restless, jetlagged sleep and startled awake in the attic bedroom next door to her cousin Emily’s room. At daybreak, she got out of bed, still tired, and stood on the bare floor at the dormer window, worrying about the miniature cows grazing in its shadow. To Susan, the tall cooling tower with its concave curves looked like a clay pot thrown on a giant’s pottery wheel, but that was her seeing it with a Berkeley kid’s eyes. In reality, the power plant was dangerous. One meltdown in England could poison the entire island, her dad, Jack, had told her. “And then where would you go? In America, you could always keep driving.” Of course, Jack would say that, safe in California. On their daytrip to Hadrian’s Wall, Susan had seen other cows scratching their rumps on rough Roman stones. Cows had been in England forever. “Seems wrong they plunked down that creepy nuclear thing so close to the cows,” she said over cornflakes at breakfast. “The cows don’t know the difference,” Emily replied. After breakfast, Susan’s mother, Kate, told Susan to grab her boots. They would go for a walk, excusing themselves from telly-watching with Aunt Carol and Emily. Aunt Carol’s favorite soap opera, Where the Hat Is, was hard to sit through, Kate and Susan agreed: Arrogant Clive was cheating on his sweet wife Pansy, and Aunt Carol made sad little noises while she watched. “We’re fitness freaks,” Kate explained, lacing up her hiking boots. “Still stuck in that California mentality. We’ll drop it in time.” “I hope not!” Susan said, following her mother out through the French doors. “Shall we walk into town?” Kate asked. That meant skirting the field where the cows idled below the cooling tower. “Let’s not,” Susan said. “Suit yourself.” Kate unlatched the gate, and the two of them stepped out into the back lane. “You looked like you could use some air,” Kate said, walking fast over the cobblestones. Susan didn’t reply, out of breath already. If Kate were honest, she’d admit she was the one who needed to escape the English relatives. For the first time, more people came to Susan’s mother to give advice than to ask for it. They treated Kate as an abandoned wife, not a newly promoted professor. Sunday, lunchtime, Aunt Sarah and Aunt Thelma had turned up uninvited. In the kitchen that smelled of boiled cabbage and starchy-steamy Birds custard, they’d folded their arms under their breasts. Aunt Thelma had shaken her head. “Such a shame, love.” Susan pulled up her parka’s hood and trotted after her mother, out of the back lane and onto the common. “Does it rain all summer?” she asked, jumping over a puddle. “Yep. What a place. This is my roots, kid. The hypodermic needles jutting out of the mud are as much a part of it as the flowerbed in front of the vicar’s cottage. Metaphorically speaking.” Kate had morphed into Professor McPhee, but at least she was talking to Susan now. Back at Aunt Carol’s she’d sink unspeaking into an overstuffed chair and stretch her legs toward the electric fire. “Brrr.” Kate zipped up her parka. “Still, only another week.” “And then...” Across lawns, across oceans, Susan followed her mother, trying not to mind, though often tired. As they mushed their way through the wet grass, the mud-stained Susan’s hiking boots with dark thumbprints. Susan raised her head, and with a tourist’s eyes sought the beauty her relatives claimed was there: the grass sloping to a pond where, behind purple heather, a black swan glided over dark water, the sky pressing down, low and gray, as water-stained as her hiking boots. Susan tried to describe her claustrophobia as though to a friend back home: “England is a dark country. I keep thinking I’ve forgotten to take off my sunglasses.” And she went blind to the scenery, seeing another country where people wore sunglasses. “I miss California.” “Tough,” Kate said and mumbled more words lost to the wind. “You’re acting more like a teenager than a mum,” Susan wanted to say. She almost looked forward to Nairobi, be Susan didn’t reply, out of breath already. If Kate were honest, she’d admit she was the one who needed to escape the English relatives. For the first time, more people came to Susan’s mother to give advice than to ask for it. They treated Kate as an abandoned wife, not a newly promoted professor. Sunday, lunchtime, Aunt Sarah and Aunt Thelma had turned up uninvited. In the kitchen that smelled of boiled cabbage and starchy-steamy Birds custard, they’d folded their arms under their breasts. Aunt Thelma had shaken her head. “Such a shame, love.” Susan pulled up her parka’s hood and trotted after her mother, out of the back lane and onto the common. “Does it rain all summer?” she asked, jumping over a puddle. “Yep. What a place. This is my roots, kid. The hypodermic needles jutting out of the mud are as much a part of it as the flowerbed in front of the vicar’s cottage. Metaphorically speaking.” Kate had morphed into Professor McPhee, but at least she was talking to Susan now. Back at Aunt Carol’s she’d sink unspeaking into an overstuffed chair and stretch her legs toward the electric fire. “Brrr.” Kate zipped up her parka. “Still, only another week.” “And then...” Across lawns, across oceans, Susan followed her mother, trying not to mind, though often tired. As they mushed their way through the wet grass, the mud-stained Susan’s hiking boots with dark thumbprints. Susan raised her head, and with a tourist’s eyes sought the beauty her relatives claimed was there: the grass sloping to a pond where, behind purple heather, a black swan glided over dark water, the sky pressing down, low and gray, as water-stained as her hiking boots. Susan tried to describe her claustrophobia as though to a friend back home: “England is a dark country. I keep thinking I’ve forgotten to take off my sunglasses.” And she went blind to the scenery, seeing another country where people wore sunglasses. “I miss California.” “Tough,” Kate said and mumbled more words lost to the wind. “You’re acting more like a teenager than a mum,” Susan wanted to say. She almost looked forward to Nairobi, be cause there, at the University, her mother would regain her power. “We won’t live in a hut,” Susan said. “I told you, the University of Nairobi is quite modern. The housing is good. And wait till we get out of the city. The birds, Susan!” They were passing a trio of pigeons sheltering from the drizzle beneath a park bench. “The plumage, the electric colors.” “Isn’t it wrong to admire wildlife and scenery in a country with hungry people?” Kate was getting soft. She criticized the “safari mentality” in others. “True, some people live in appalling conditions. You’ll see beauty but you’ll also see things that will hurt.” As though nothing had hurt Susan before. “You’ll witness the eternal struggle of humans fighting to dominate nature, fighting for food, fighting to assert themselves against disease and drought.” Susan and Kate had marched beyond the common to the local dump, or “tilt,” and now walked along the crest of the hill, the pond below them on one side, a sea of garbage on the other. Here was nature dominated. Was this what Kate wanted? “I’m sorry you miss California, kiddo.” “I miss Dad, too.” “I think the divorce was inevitable. Where there’s love there’s often hate. In time. Peace is nice, but more often life’s a war. Speaking of eternal battles.” For Kate to pretend she had chosen to fight was a lie, though. “He left you, Mummy. It’s his problem. Not yours. Not your war.” If only Susan could say that. “I do want you to have some fun on your holiday.” Kate and Susan trudged down the back lane again until they came to Aunt Carol’s gate. “Please not the stinky indoor swimming pool again.” “Right.” Kate pinched her eyebrows together. “Don’t suppose the sheepdog trials would grab you?” “Give it up.” They pulled off their boots at the French doors. Inside, the soap opera’s credits were rolling off. Susan went to the window and pushed aside the gauzy white curtain. Homesickness for Berkeley, for her American dad, clutched at her throat. She swallowed, squeezing tears into her eyes. Why did she have to travel around the world because her parents’ love had turned to hate? Why couldn’t they just get on? According to Kate, the Kenyans fought an eternal struggle for their survival. What did Jack and Kate fight for? Low clouds scuttled over the field, and the cows drew closer together. Half a dozen calves lounged on the ground, while their mothers stood over them, protecting the calves from what? The wind, maybe. Fat lot of good they’d be in case of nuclear disaster. Emily was right, though, the cows and their calves didn’t know the difference. “That’s what makes you human,” Kate would say. “You are aware of your struggle.” “What struggle? I am being dominated,” Susan could have replied. “All I can do is stick it out until I’m old enough to be on my own.” Behind Susan, Kate said, “Susan and I were discussing what to do with the rest of our holiday.” Susan turned back to the room. “We could have a picnic. Out there on the grass.” Emily was setting empty teacups on a tray. “Under the ‘creepy nuclear thing’No thanks.” “Too damp,” Kate said. “I’ll go on my own then.” Kate glanced down at the newspaper on the coffee table, her brown eyes scanning the headlines, not much of a listener, though she liked the sound of her own voice. “What shall you have for this picnic?” Aunt Carol asked. “Shall I whip you up some egg and cress sandwiches?” “No. An American sandwich,” Susan said, though she’d have to walk into town past the cows to pick up the groceries. “Turkey. With mustard and mayo.And—” Aunt Carol’s hands went to her hips. “And?” “Tomato and lettuce.” Susan counted the ingredients on her fingers. She finished on the first finger of her second hand. “And pickles.” Aunt Carol shook her head, then smiled. “I’ll give you my rubber-backed blanket so you won’t mind the damp.” “Watch out for cow pies,” Emily said. Would they all peek out of the window at Susan sitting in the drizzle? Too late to back out of it now. She would picnic alone in the field with the cows: nature dominated, but also nature enduring.

Four Seasons BY Melissa Ren

Twice as Much and Twice as Hard BY Lillian Heimisdottir

Twice as Much and Twice as Hard BY Lillian Heimisdottir

冬天 Winter

Hàorán Wong was in the winter of his life, living in a cookie-cutter room painted in buttercream and outfitted with standard-issued furnishings for ease of efficient turn-over. His only belonging was a carry-on suitcase, which stood upright in the wardrobe, still filled with a few clothes he never bothered to unpack. Children’

冬天 Winter

Hàorán Wong was in the winter of his life, living in a cookie-cutter room painted in buttercream and outfitted with standard-issued furnishings for ease of efficient turn-over. His only belonging was a carry-on suitcase, which stood upright in the wardrobe, still filled with a few clothes he never bothered to unpack. Children’s giggles echoed in the hallway, causing his chest to ache. Another grandparent’s birthday, he assumed. Or maybe it was the weekend when visitors came in troves. If he had the energy to get up from the armchair, he would have closed the door. Instead, he turned off his hearing aids and stared out the window. The parking lot wasn’t much of a view, but it was the only view that mattered to him. He hoped for the day he’d glimpse his daughter among a sea of cars. Ming-Yue was a grown woman now, barely recognizable, married with children of her own. Two, the last he saw, though it’d been six years since they’d seen one another at his wife’s wake. He still called Wen his wife, having never signed the divorce papers in hopes she’d find her way back to him. She never did. All of Wen’s closest friends, friends he didn’t recognize, attended her funeral ceremony. There, Hàorán met his two grandsons for the first time. He never got their ages, but assumed two and four from their size. The eldest looked just like him: a narrow face with sharp eyes. Named after his grandmother, Warren stood tall by his mother’s side as she clutched her youngest in her arms. Warren bowed three times without prompting, to pay his respect to Wen. As he stepped away from the altar, the boy flicked his gaze to meet his grandfather’s eyes and smiled. As if they knew one another. On one of the saddest days of Hàorán’s life, his heart was finally full.

秋天 Autumn

During the Mid-Autumn Festival, when most celebrated a fruitful harvest under the full moon with their loved ones, Hàorán spent the evening with a woman nearly half his age, someone he’d met one night while drinking báijiǔ at a bar. Her thin, yet shapely figure first drew him in. But then she spoke, her sultry voice lingered in the air. Smooth, like jazz music. Sexy and full of want. She leaned in, clasping the stem of her glass as her knee brushed against his. A sensation effervesced within him. She smiled with teasing eyes. And that’s all it took. When they were together, he’d felt as young as her. Stronger. Desirous. The man he should have been. Not a husband to a nagging wife. When did he lose sight of who he was? She’d massage his shoulders in bed like a dà lǎo, a big shot, and he started to believe it. They dined at fancy restaurants he’d never taken Wen. Splurged on jewellery he’d never given Wen. Sipped on cocktails at jazz clubs while Wen and MingYue were sleeping. That night, as lanterns filled the sky and families gazed at the moon, Hàorán hand-fed his lover the mooncakes he bought for his daughter for the Mid-Autumn Festival. After all, MingYue’s name meant ‘bright moon’ after the auspicious celebration. She was turning eleven in a few days. He’d replace them tomorrow, he thought. On the cusp of the morning hour, Hàorán left his woman’s apartment in the city as he so often did, taking the longer route back to the suburbs. As he drew closer to his home, a heaviness filled his chest. The warmth he’d felt only hours ago evaporated into the crisp night. The lights to his house were on, brightening the entire street. His heart thrummed against his ribs as he pulled in. Wen had waited up for him. The night was long from over. For a moment, he considered turning around, but he’d have to face Wen, eventually. He took a breath before opening the door. All was quiet inside. Wen wasn’t sitting on the couch as he expected. She wasn’t sound asleep in their bed either. And neither was their daughter. Their closets had emptied. Suitcases with it. Wen and Ming-Yue were gone. She’d finally left him

夏天 Summer

Only days into the season and the summer mugginess flooded the house, suffocating Hàorán and clouding his chest. Everything stuck to his body: the newspaper to his forearm, his thighs to the vinyl chair, the hairs to the back of his neck, the skin-to-skin of his underarms. His muscles tensed as he glared at the monthly bills scattered across the kitchen table. He dropped his head into his palms and groaned. Hadn’t he just paid the bills? Where did the time go between months? He opened up the cheque book and scribbled the date, amount, signature. Date, amount, signature. Over and over. When did life become so cyclical? So monotonous? Working a job he hated, paying a mortgage for a house he didn’t want, living in a neighbourhood too far from the city, married to a woman he wasn’t sure he loved, preparing for a family he didn’t have. Did he even want children? He was in the prime of his life, and yet, responsibilities had aged him. Was this all there was to living? Eat, shit, sleep, repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Not that long ago, Hàorán had dreams of travelling the world and discovering new cuisines. He wanted to read more books, watch foreign films, listen to jazz music. Maybe grow his hair long and take up surfing or cycling. He yearned to just be. Marriage had changed him, that much he knew, and the truth made his insides rot. Wen entered the kitchen, a small smile touching her lips. She placed a cardboard bakery box knotted with a red string on the table. Inside were six perfectly round mooncakes, its shape a symbol of family unity. He hated those things. She slid a hand over her belly, her cheeks shaded rose. With wistful eyes, she whispered, “You’re going to be a father.”

春天 Spring

Spring blossomed the city with buds, colouring the trees with peas and gardens with confetti. Hàorán cut across the quad to enter the campus bookstore to collect reading materials for his last semester. He was passing through the English Literature aisles when a girl caught his eye. Long black hair, a gentle face, a smile that lit up the entire room. She stood by herself, leaning against the bookshelf as she laughed while reading. Hàorán’s chest warmed. He watched her from the gap between two aisles. She flipped the page and giggled once more. The corner of Hàorán’s mouth ticked up. Beautiful. She snapped the book closed and met Hàorán’s eyes. He snatched the first book at arm’s length and pretended to read the back cover. He could feel her watching him. His heart rattled in his chest as he counted the passing seconds. Once he hit thirty, he chanced a glimpse. The girl wiggled her fingers in a wave. Heat rushed to his cheeks. Hàorán contemplated waving back, but he couldn’t feel his arms. Or his legs. She pulled her backpack over her shoulder and walked straight toward him. A lump in his throat prevented him from speaking. Instead, he managed an awkward grimace. The girl smiled, bright and innocent. He’d made her smile. And that knowledge sent a thrill through him. He wanted to do it again. “Do you always come in here and pretend to read so you can stare at girls?” She smelled like a strawberry milkshake. His eyes rounded. “I’m just teasing.” She tucked her hair behind her ear with a graceful hand. “I’ve never seen you in this aisle before. I’m usually the only one.” She’d noticed him, too. With a sudden confidence, he said, “I’m Hàorán. And I wasn’t staring at all the girls. Only one.” She bit her lower lip, blushing. “Together, our names could be summer.” Hàorán titled his head. “My name is Wen.” Warm. His name meant ‘overwhelming’ and in that moment, he wanted nothing more but to spend a summer with her. And every summer after. Hàorán’s entire life was ahead of him. ☐

Twice as Much and Twice as Hard BY Lillian Heimisdottir

Twice as Much and Twice as Hard BY Lillian Heimisdottir

Twice as Much and Twice as Hard BY Lillian Heimisdottir

Once upon a time, in a faraway land, lived a king and a queen. The king was haughty and supercilious, but the queen was wise and resourceful. They had no children who would inherit the kingdom, so one day the queen suggested that they should search for an heir among the young people of the land to fi nd a suitable successor. “That’s an e

Once upon a time, in a faraway land, lived a king and a queen. The king was haughty and supercilious, but the queen was wise and resourceful. They had no children who would inherit the kingdom, so one day the queen suggested that they should search for an heir among the young people of the land to fi nd a suitable successor. “That’s an excellent idea,” the king said in his boastful manner. “We’ll send some young men on a quest, and the worthiest of them shall get the kingdom after our days.” “Why only the young men?” the wise queen asked her husband. “Shouldn’t the young women of the kingdom be allowed to participate in the competition?” At this, the king laughed very loudly and said: “This is such a ridiculous idea, that I don’t know if you are even serious about it. But I say this: If a girl should outperform all the excellent young men in this country and emerge as the winner in the quest, she doesn’t even have to wait for me to die to take over the kingdom, but can take the throne immediately.” The news of this royal decree spread throughout all the kingdom. Everywhere, young men were eager to prove themselves in an attempt to become heir to the throne. Some of the young women also expressed interest in the competition, but they were laughed at and soon gave up all hope of being able to compete. However, in a small village at the edge of the forest, there lived a young girl who was curious and adventurous. The girl loved to explore and discover new things, so she asked her parents if she could go on the quest and try to become the heir of the kingdom. “You can go,” said her mother. “But remember that you will have to work twice as hard and twice as much if you want to be as good as all the young men you are competing with.” “And even that might not be enough,” her father thought, but he said nothing.

The Halls of Wisdom

So the girl left home and went out into the wide world in order to compete for the kingdom. She soon came to the Halls of Wisdom, which were designated to be the fi rst part of the competition. Here the girl read all the books she could lay her hands on and listened to lectures from famous wise scholars from all over the world. She read twice as many books as everybody else and stayed twice as long in the library to work on her assignments. By doing so, she came out on top of her group and did better than all her competitors. As soon as the king realized how well the girl was doing, he urged her adversaries to torment her and keep her apart from their group in an effort to make life tough for her. He challenged the men to make her life as diffi cult as they could, “Are you men going to allow this female to outperform you?” But the girl would not let herself be discouraged. She read twice as many books as everybody else, and attended twice as many lectures as her competitors, and when this part of the competition was over, the king himself came and awarded her recognition for her efforts. “You see,” said his queen to him. “Young women can compete just as well as men.” “That might be true for this part of the quest,” answered the king in a haughty voice. “But let’s see how she’ll do in the next stage.”

The Fields of Labour

The girl said goodbye to the Halls of Wisdom, with some regret because she had liked the place very much. She went on until she came to the Fields of Labour. Here all kinds of tasks awaited the competitors, but the girl mastered them all. She worked twice as hard on her projects and stayed twice as long at her workplace than everybody else. As a result of her diligent efforts, the girl did the best work and surpassed all her rivals. When the king saw how well the girl was performing, he encouraged her rivals to harass her and keep her out of their group in order to make things more diffi cult for her. “Are you guys going to let this little girl outmatch you?” he said to the men and goaded them to make her life as challenging as they could. But the girl continued to work twice as hard and twice as much as everybody else. The king watched her efforts from afar, and although it wasn’t easy for him to admit it, he could not but acknowledge the girl’s effi ciency. “You see,” said the queen. “Women can do just as well when it comes to working. The king had to admit that she was right, but he wasn’t happy with it. “Let’s see how she’ll do in the fi nal undertaking,” he said and laughed maliciously. The queen saw the king was up to something wicked and she became worried. She went off, immersed in deep thoughts, dreading the worst.

The Dominions of War

But the girl continued her quest after having said goodbye to the Fields of Labour, where she had had such great success. It wasn’t easy for her to leave her newfound colleagues behind, but she knew that she had to go on in order to fulfi l the requirements that had been set by the king. She had to prove that she was a worthy leader in order to be able to inherit the kingdom. But the king didn’t want to see the girl win the competition and succeed in the quest, because that meant he would have to resign his throne to her while still alive. Also, he would have to admit to his queen that she had been right about women competing successfully, and he liked that even less. So he put on his armour and commanded that all the young men should be dressed in uniforms and made to carry weapons. Then he said to the girl: “We are going to war now. We will raid and burn many villages. Will you burn twice as many villages as your competitors?” The girl gave no answer, so the king and his soldiers just laughed at her. The king then added: “In this war, we will kill many men. Will you kill twice as many men as your challengers?” The girl remained silent and the soldiers laughed. Finally, the king asked: “In this war, we will molest many women. Will you molest twice as many women as everybody else?” He said this in a cruel and vicious voice and the men roared with laughter. The girl now hung her head, for she knew that she would not be able to do these things, which meant that she had failed in her quest and that all her hard work had been for nought. “You see, little girl,” the king said triumphantly. “This is the way of the world. You can work twice as much and twice as hard as everybody else, but if you lack the will to conquer people in war you can never rule a kingdom like this one.” And with that, he made himself ready to lead his young soldiers into battle in order to raid and pillage, kill and molest his victims. But as he was marching off, the queen arrived and with her all the inhabitants of the towns and villages the king had planned on attacking. They had united under the leadership of the wise queen and together they outnumbered the troops of the king by far. The king saw that there was no way he could win this battle, so he retreated and left his kingdom in charge of the queen. “You have proven yourself to be worthy,” the wise queen said to the girl, “and you shall rule the kingdom from now on.” The king, who had to resign his throne to the girl, was out of a job. To keep himself busy he spent the rest of his life playing a silly game in which he had to use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strikes as possible. T he girl however, grew up to be a beautiful woman, who, with the aid of the wise queen, ruled the kingdom in an enlightened and judicious manner. She married a handsome, if somewhat useless man, who cut a fi ne fi gure beside her, and the people in the land were glad to live under her sovereignty in every area of life. She made sure that girls and boys had the same opportunities when it came to studying and working and that no girl had to work twice as much and twice as hard to get to where her male counterparts were. For this, she was loved and respected by her compatriots. They all lived happily ever after and if they haven’t died then they are still living today

Trace

Unplayable Lie by James Blakey

Unplayable Lie by James Blakey

High on a cliff on a remote island in the wilderness known as the Boundary Waters in Northern Minnesota, the gray wolf slowly gnawed at dregs of what was once a large deer. Overhead the late afternoon sun threw long shadows from towering pines across the rotting carcass. He could not know the name of his disease that attacked his parasit